Eight Ways the OPC Cardinals were More Gutsy than Any Men’s Team

1. Practiced every day starting at 4:00 a.m. in a freezing-cold field house

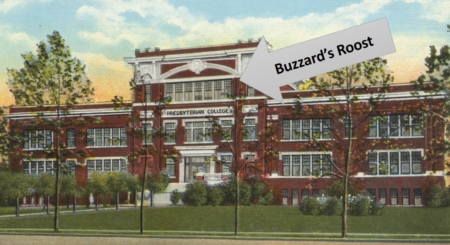

For the first three weeks of basketball practice, before they had the field house, thirty-five girls had found limited space to learn passing drills and shoot free throws in the college’s small half-court gym on the fourth floor of the administration building, nicknamed the Buzzards’ Roost. The players kept the windows open, and the stinky pigeons that roosted beneath the window eaves often hopped inside. The girls would chase them out, but the birds kept leaving heaps of droppings across the floor. Unlucky freshmen were appointed to sweep up.

Knowing they needed a better place to practice, Coach Babb sought the advice of O. L. “Runt” Ramsey, coach of the Savages, the boys’ basketball team at nearby Southeastern State Teachers College. Ramsey offered the use of their field house when he was sure his boys wouldn’t be using it—from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. every morning. After arriving at the field house, the Cardinals often clasped blankets around their shoulders because it felt like an icehouse. The heat wasn’t turned on until 5 a.m. every day when the caretaker finally arrived.

2. Traveled in an ancient, crank-start bus that was always stalling and needing a push

2. Traveled in an ancient, crank-start bus that was always stalling and needing a push

Long as a limousine, with three doors on each side, the ancient nine-seat crank-start bus shed oil in dark puddles. With its fading red paint and erratic engine, the OPC bus was a dubious form of transportation.

The old bus might have looked like this one on the left.

Juanita “Bo-Peep” Park, a sophomore guard and vice-president of her college class, helped the school out by driving the bus and even making the repairs. Her family lived on a farm a few miles east of Durant in an unincorporated community called Blue, named after the nearby Blue River. She had nicknamed herself at age five after the same Little Bo-Peep from the fairy tale because her family raised sheep and she had loved the girl in the story. Her father taught her to drive when she was eleven, mainly because she was tall for her age and could reach the pedals easily. After six years of driving a hay truck, Bo-Peep was an expert, but on this frigid morning the bus refused to start. The engine revved up as if it were about to turn over, then sputtered out with a nasty cough. The smell of gasoline leaked into the morning air. She was forced to hop out, crank the engine, hop back in, and push the starter.

3. Stood up to the first lady, Mrs. Herbert Hoover, who fought against women’s right to play competitive basketball

Both the secretary of war and the secretary of navy from President Warren Harding’s cabinet contacted Lou Henry Hoover, wife of Herbert Hoover, the current secretary of commerce, and asked if she would lead a new women’s unit within the National Amateur Athletic Federation. The NAAF was formed by the U.S. government after World War I to improve levels of fitness in the nation’s youth. Hoover demanded a separate group altogether for women, and she called it the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Federation, or just Women’s Division. Its directive: to combat the bad tendencies of competitive women’s athletics and promote a national interest in the right kind of sports and games for girls. Hoover warned against the exploitation of girls and women participating in sports without proper supervision. She labeled the general tendency to copy boys’ athletics with an emphasis on setting records and having championships “a cancer that must be killed.”

The division would protect athletic activities for girls and women from the evils of commercialization and the win-at-any-cost ethos by abolishing travel to other cities, gate receipts, and finally, the leering fans who lost themselves while cheering for their favorite teams. Young women should not be forced to sacrifice themselves for a winning team and would never again play in front of a crowd.

4. Battled against other traditional expectations of ladylike behavior and the class perceptions that came with it

4. Battled against other traditional expectations of ladylike behavior and the class perceptions that came with it

What if a middle-class girl on her way to a prestigious university decided she liked the smooth-leather feel of a softball, enjoyed tossing it around, and got herself a horse-hide mitt and joined a league? Or maybe she was used to outdistancing her brothers when they raced down the block to school as kids, and her favorite shoes became the sneakers she wore when she sprinted around the high school track. The sight of girls expertly running the bases or clearing a hurdle was not met with approval.

Besides developing the more masculine qualities of strength, daring, and endurance, these sports attracted the coarse beer-drinking working-class crowd who populated the industrial teams, and God forbid a cherished daughter would practice softball or track-and-field over dancing the foxtrot. But the worst game a girl could ever get good at was basketball. Maintaining a sweet smile in the midst of an intense battle on the court was rare to impossible.

5. Paid their own way through ticket receipts and sponsorships

5. Paid their own way through ticket receipts and sponsorships

Since the team didn’t have school funding, Coach Babb and OPC team members attended business club luncheons and sought additional financial assistance from local businesses that, for a few dollars, could attach their names to game-day programs and receive good publicity in the newspapers. The businessmen, all dressed in wool suits with silk ties, watched the girls while they sang the school song (in the same tune as Cornell’s school song) over the microphone, with first-string-substitute Buena Harris’s clear soprano leading. The daughter of a prominent Cherokee chief from Pryor, up near Tulsa in northeastern Oklahoma, Buena was also vice president of the campus Utopian Literary Society and had just been elected secretary-treasurer of the sophomore class. The businessmen seemed quite impressed. Never in her wildest dreams had any player imagined that she’d be charming bankers, store owners, and automobile dealers so that they might help fund a woman’s basketball team.

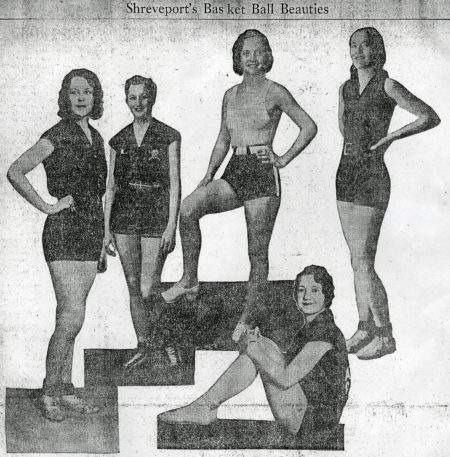

This photo is from the tournament souvenir program distributed at the 1932 AAU national tournament in Shreveport, LA.

6. Might be asked to compete in a beauty contest

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), who sponsored women’s competitive basketball, encouraged teams to recruit and train highly skilled female athletes. Only the best players and teams would attract crowds. At the same time, the AAU had to uphold society’s image of the feminine ideal—a woman who was poised, graceful, and beautiful. Because of the onslaught from the Women’s Division and the public’s nagging idea that working-class female athletes were mannish, AAU leaders staged an event during the national tournament that would exhibit their players’ feminine charms—a beauty contest!

Each team selected its most beautiful player to compete. Some girls considered it like a sideshow that provided certain types of entertainment. Usually, athletes didn’t care about the beauty pageant as long as they could keep playing basketball. The Cardinals’ only championship at an AAU-sponsored tournament occurred in 1930 when team captain Verna Montgomery won the beauty contest and made headlines as the Cardinals’ “Brunette Beauty Queen.”

7. Better at passing the ball

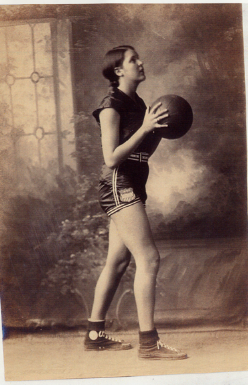

Special guidelines were adopted for women’s basketball in 1901. Players referred to these guidelines for women as “girls’ rules.” By 1922, women’s basketball teams contained six players instead of five. The additional player was a guard. During a game, girls did less scoring, not because they were less aggressive or poorer shots than boys, but because their extra player made their guarding tighter. The court was divided in half, the offense on one side, defense on the other. Only one below-the-knee dribble was allowed. To compensate, women became the most expert at passing the ball. The guards had to finesse the ball, pass with flow and continuity, and dominate the opposing team in order to feed it to their offense on the other side of the court.

8. Beat the greatest athlete of her generation, Babe Didrikson

Babe Didrikson was the crack shot who played at forward for the Dallas Golden Cyclones, the Cardinals’ greatest rival. In the summer of 1931, Didrikson came to national prominence by taking first place in eight events at the AAU national track meet. In 1932, she astounded the world with her track-and-field performance at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles. She won two gold medals, in the javelin and hurdles, and a silver in the high jump. Sportswriters labeled her the greatest female athlete of all time. She went on to become a sensation on the golf course and the leading female player of the 1940s and ’50s.

Click on the picture below to view the Babe Didrikson museum webpage.